Running Biomechanics: The Lean

It becomes discouraging when one injury follows another and yet another. Sometimes it can seem that the cost of running for our health, appearance and mood, is paid for by a series of injuries. Runners often describe each injury as a separate issue and event, but a physical therapist that specializes in human movement almost never sees injuries as disconnected. Understanding the connection between injuries can often be evaluated through a biomechanic perspective. This perspective allows us to review the larger picture of why some tissues become over-stressed and how we can change mechanics to decrease pain.

When we learn more about each person’s daily postures, physical stresses and individual running mechanics, we discover patterns. The patterns reveal the overuse of some muscles and under use of others, they indicate where more stress is created on tissues that can become injured. While injuries like, patella femoral pain, plantar fasciitis and lower back pain sound very different, they may be associated with the same underlying faults. When a runner takes the time to learn about their patterns and how they move while they run, they can take control of their technique and limit their injuries. In this article, the first of several, we will take a close look at body posture during running.

The best place to start a running gait assessment is to look at the runner’s body posture or lean. Have a friend film you as you run on the treadmill and take a good look at your positions. Assess your trunk posture and see where it comes from.

Normal forward lean should be modest and allow your run to feel like a controlled fall forward. The forward lean should come from your ankles (not from leaning at your hips - like you do when you are about to begin to sit into a chair). Think about the forward lean from the ankles, like the early stage of the Michael Jackson ‘dancing lean.’

Use your body to experiment with your mechanics. With your shoes on, stand up with shoulders over your hips, walk upright, try leaning back, then try leaning slightly forward. Ask yourself: how do my joints feel? How far can I reach my foot in front of me? Then, try it again walking barefoot on a firm floor and discover what changes within your body.

One of the major differences you will find in this experiment is when you are upright, and particularly when you are leaned back, you can reach your foot much farther in front of you. With shoes on it is easy to take a long stride with a heavy heel strike. However, when you lean forward from the ankle, you cannot reach as far in front of you with your foot, there is no time since your foot must control your body moving forward to prevent you from falling. This style of walking requires more push from your muscles than pull. Now, lean back again and feel your hamstrings pulling your body forward. Your walking form translates to your running form.

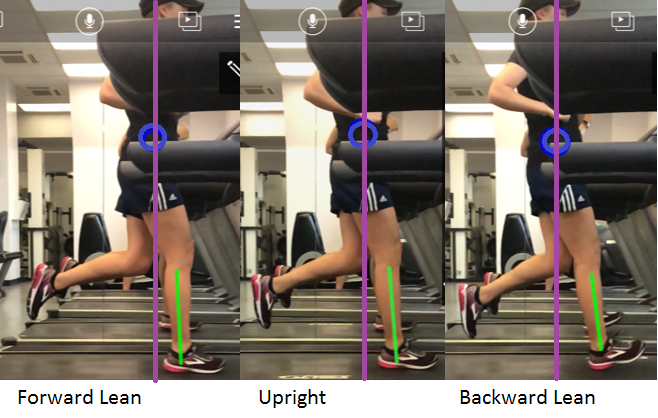

When running, an erect or backward lean posture drives the foot further forward in front of the body. In the photographs, notice how much treadmill space there is between the purple line and the heel. Notice the alignment of the lower leg during the foot strike. The ideal is closer to vertical.

A runner’s increased foot strike in front of the body causes a ‘breaking force’ which can be seen in an extra wobble at the knee or excessive motion in the foot/ankle (into pronation or supination), or a loud heel strike. With a backward lean, the demand can be greater on structures like the quad, IT band and plantar fascia. The way forces spread out in the body depends on each person’s skeletal structure and joint alignment, their unique muscle strength, muscle length and body segment ratios. Personally, I find that a backward lean running position causes me to have: a heavy heel strike, long stride, increased ankle pronation, excessive knee valgus and hip drop. For me, personally, leaning back is injury risk galore!

Not everyone will run the same, nor do they need to. Improving your forward lean comes with risks as well. It may increase work at your foot and ankle (increasing stress on the bones of the foot, increasing work from the calf), and if done in excess, or if you are leaning from the hips (instead of the ankle), it can increase stress on your low back.

Use your good judgement and have a friend film you with their phone to see if you are doing something that looks odd or feels bad within your body. You should not make a running change that increases pain. The pain is telling you that you need to make a different change. Learning about your body’s movement mechanics and unique aspects of alignment can give you the freedom to control your pain and enjoy your running!

- Ann Crowe, PT, DPT, MS

This blog is not intended as medical or professional advice. The information provided is for educational purposes only and is not intended to serve as medical or physical therapy advice to any individual. Any exercise has potential to cause injury or pain if it is incorrectly done or is not the right exercise for an individual’s medical or physical problems. You should consult with a physical therapist or medical provider for individualized advice.